GTM Zero to One: Go Deeper on Competition with Value Chain

To understand how your industry will evolve and inform GTM

Day 10 of writing.

Competitors. It’s something we as leaders think about and include in our pitch decks as a 2 x 2 (with our company in the upper right of course) or a feature checklist with ours with the most checkmarks.1

A missed opportunity is to really look more deeply at value chains, whether you’re a later-stage org looking at new product opportunities or an early-stage founder.

🔗 My Favorite Way To Think About Value Chains

Two excellent thinkers are Clayton Christensen2 and Ben Thompson via Stratechery3.

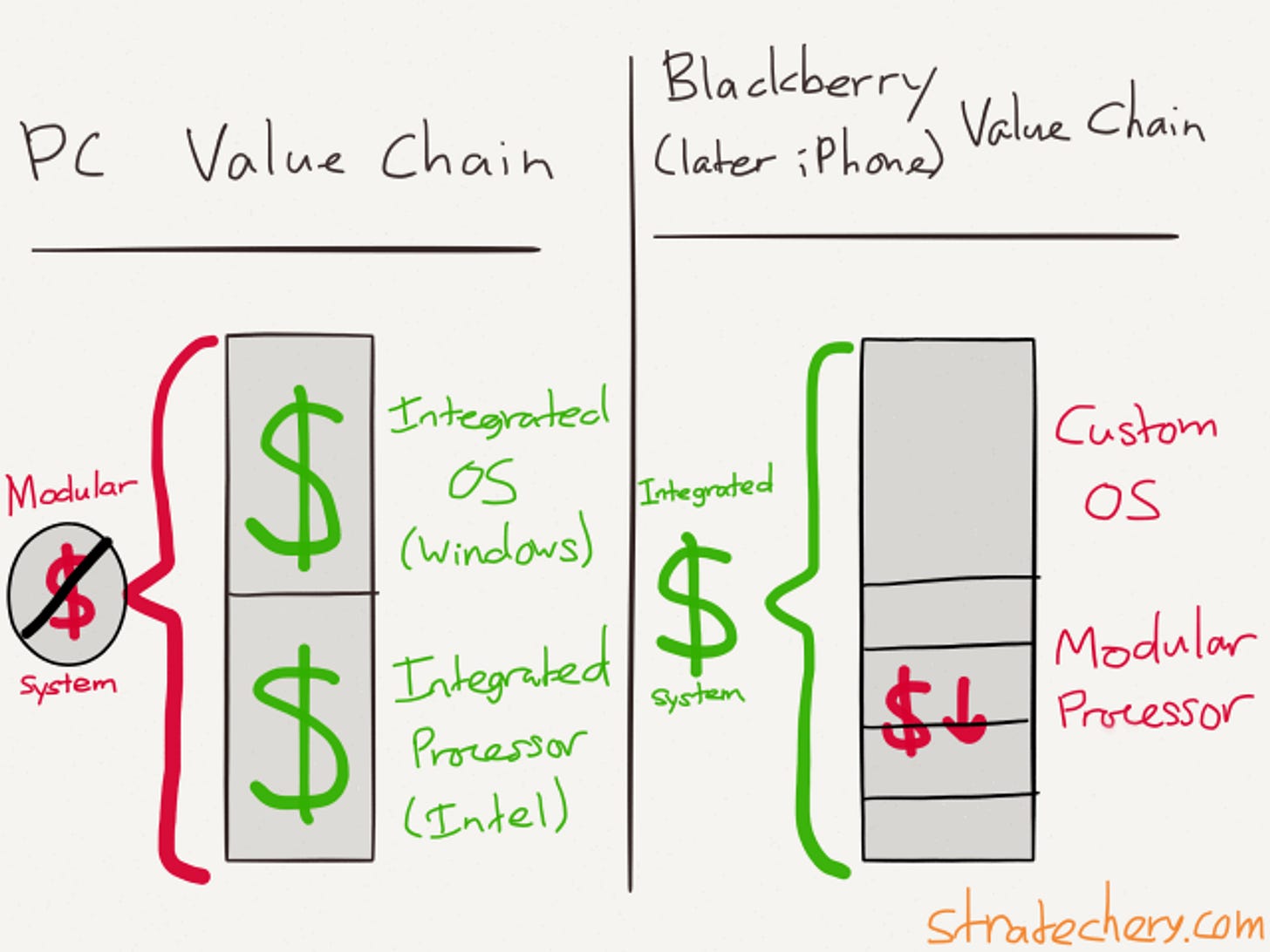

To understand how an industry might evolve, we have to know where players (incumbents/big tech and upstarts) have an opportunity to compete and what part of the value chain they’re in, to know if you’re going to compete and win on brand/product (integrated and where value goes) or on cost/performance (modular and where value gets commoditized).

🐣 Why This Matters Early Stage

In the early days, yes it’s helpful to know your competitors, especially because :

you’re likely going to need to convince customers to switch from one (unless it’s still a mostly manual process/workflow you’re going after) and

you need to know where they’re weak and where to prioritize for your the product roadmap.

But here’s why I’d push you to also look at value chain

One if you’re vying for market share in a tough industry

(e.g., K12 B2B edtech in the US)

Two, if/when you’re looking for partnership angles and channels to drive growth

(e.g., Tribe AI with cloud providers wanting their customers to get AI into production and private equity funds wanting their portcos to do the same)

Three, if you’re competing in a space where the landscape is changing daily

(e.g., AI, VR/metaverse)

🐓 Why This Matters Later Stage

This is probably obvious, but you’re competing on a specific hypothesis and shifts in the landscape become increasingly moves you need to try and predict (like chess) so you’re making the right strategic bets.

Example

I’ll give an early example in AI:

Let’s say you’re Magic School (not my client or any relationship):

You’ve just raised a Series A Round (yay!).

Over 2 million educators have signed up for the platform, over 4,000 schools and districts have joined us as partners, and MagicSchool is the fastest growing technology platform for schools ever. Not too shabby.

What is the value prop and delivery thusfar? Are they retaining? Which workflows, tools, and features are they leveraging most?

How can they expand existing contracts? There are both sales and product-driven approaches to this.

Sometime in the future: I’ll share an example of how I tried to break this down even further for the AI industry as an example.

The Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits, from The Innovator’s Solution

Formally, the law of conservation of attractive profits states that in the value chain there is a requisite juxtaposition of modular and interdependent architectures, and of reciprocal processes of commoditization and de-commoditization, commoditization, that exists in order to optimize the performance of what is not good enough. The law states that when modularity and commoditization cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.

Computers: If you think about it in a hardware context, because historically the microprocessor had not been good enough, then its architecture inside was proprietary and optimized and that meant that the computer’s architecture had to be modular and conformable to allow the microprocessor to be optimized.

Mobile: But in a little hand-held device like the RIM BlackBerry, it’s the device itself that’s not good enough, and you therefore cannot have a one-size-fits-all Intel processor inside of a BlackBerry, but instead, the processor itself has to be modular and conformable so that it has on it only the functionality that the BlackBerry needs and none of the functionality that it doesn’t need. So again, one side or the other needs to be modular and conformable to optimize what’s not good enough.

Did you catch that? That was Christensen, a full four years before the iPhone, explaining why it was that Intel was doomed in mobile even as ARM would become ascendent.